Current Exhibits

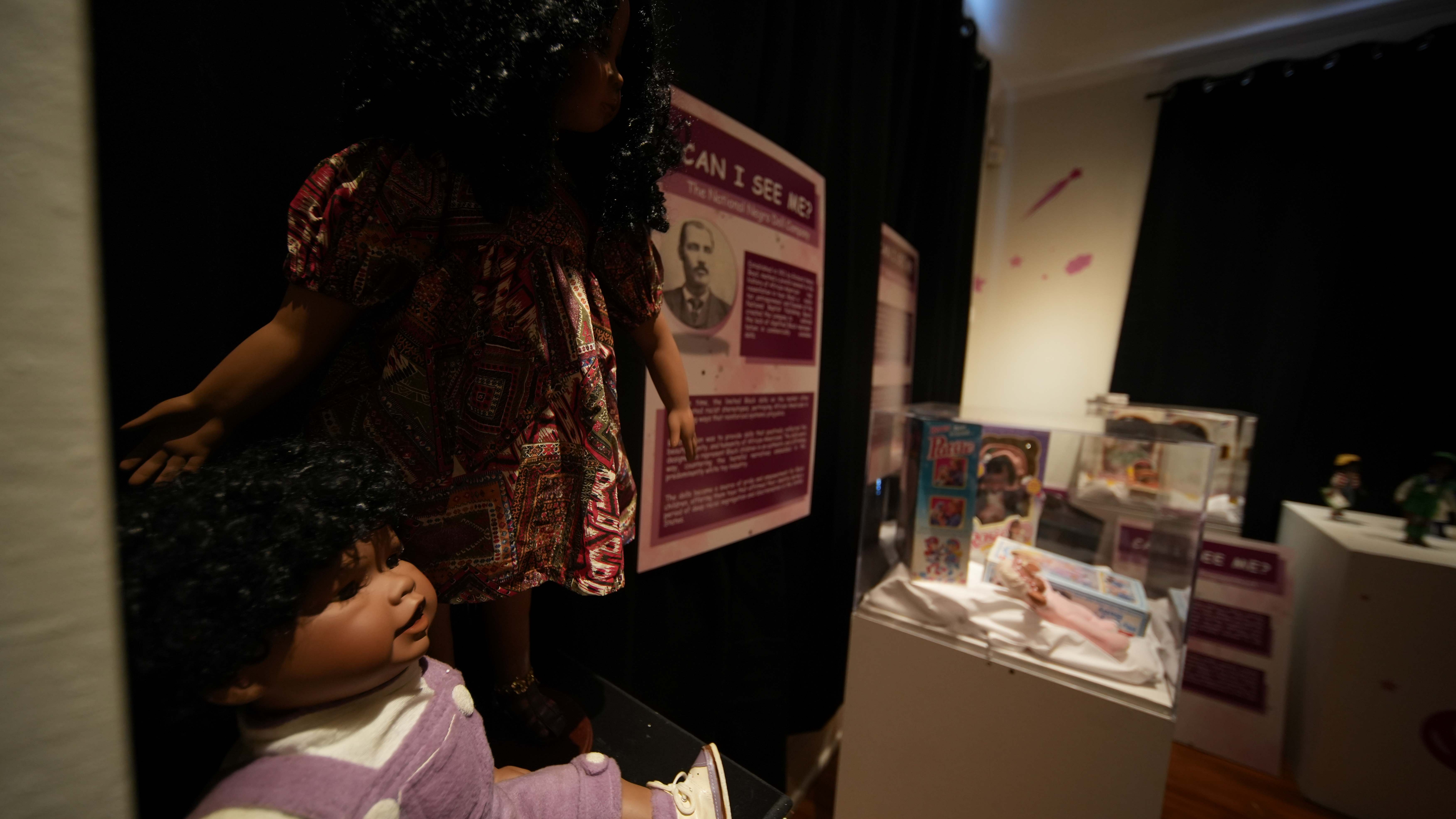

BEYOND BLACK BEAUTY

AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN, IMAGE-MAKING & RESISTANCE:

A MULTI-PART INSTALLATION

Curatorial Statment

Timothy A. Barber, Director

Beauty is both a mirror and a battleground—a space where identity, history, and culture converge. Beyond Black Beauty explores the evolution of Black beauty standards, self-expression, and representation, moving beyond mainstream ideals to embrace a narrative shaped by resilience, pride, and artistry.

The rise of Black beauty pageants, including the legacy of Miss FAMU, was an act of defiance and self-determination. When traditional pageants rejected Black contestants, communities created their own platforms to uplift Black womanhood, celebrate intelligence and grace, and redefine what it meant to be beautiful. These pageants cultivated role models and leaders, proving that beauty was not just about aesthetics but about culture, confidence, and social change.

Artists and scholars also shape the conversation. Sandro Miller’s Crowns: My Hair, My Soul, My Freedom reclaims the significance of Black hair as a form of identity and heritage, paying tribute to the rich textures, styles, and traditions that have long been politicized yet remain symbols of beauty and resistance. Steve Allen’s scholarly exploration of Afrofuturism situates Black beauty in a visionary space, where aesthetics merge with science fiction, liberation, and cultural evolution. His work reminds us that the future of Black beauty is limitless, shaped by history yet unbound by it.

Through historical artifacts, photography, fashion, and conceptual art, Beyond Black Beauty challenges perceptions and celebrates the power of self-definition. This exhibition is not just about how Black beauty is seen—but how it is claimed, honored, and reimagined.

|

|

|

Miss FAMU and the Aesthetics of Excellence

BY Dr. Kimberly Brown Pellum, Curator

Within the African American experience, two key pursuits have shaped ideas about racial progress: formal education and the freedom to define how we show up in the world. Existing precisely at this intersection of African American academic aspirations and collective image-crafting is the tradition of Black College Queens.

After slavery, national media deepened its commitment to promoting gendered and racialized stereotypes such as “Jezebel” and Mammy.” American consumers welcomed and enjoyed the fabricated characters that appeared in popular shows and movies. These stereotypes leaned on phenotypical distance from whiteness, lack of societal status and lies about sexual morality. The Jezebel was loud and offered herself to almost anyone. Mammy was usually portrayed as simple-minded, dark-skinned, round body-type, with plump red lips, wearing a headscarf and living in service to white families. Aunt Jemima, an updated version of the Mammy character, became such a popular image used on pancake mixes and housewares, it became one of the longest continually running logos in the history of American advertising (130 years). The Herlong Packing Company of Leesburg, Florida used “Mammy Brand” labeling on its citrus crates and Disneyland ran the “Aunt Jemima Kitchen” as a tourist attraction for 15 years, from 1955 until 1970.

As a counter to such stereotypes, African Americans long produced their own pageants as a type of race work. It allowed them the opportunity to express their own ideas about themselves and their own definitions of beauty and excellence.

What does excellence look like? It looks like the Black College Queen tradition, which epitomizes the ways Black people espouse education and the broad lens through which we see beauty.

NOW OPEN THROUGH DECEMBER 16, 2025

Jim Crow and the Old South Gallery

The Upper Room Church Gallery

Marching 100 Hall

Medical Gallery

From Slavery to Freedom Gallery

African Gallery